Launching the newly-created Fitzglen family on their maiden voyage in Chalice of Darkness, I trawled a great many legends to provide them with a plot.

There is, of course, an abundance of material when it comes to legends and lore and myths. Some might be true, some might be heavily embroidered, and a great many are probably outright fiction. But most of the stories can be used as the base of a plot – especially a plot involving a family who are proud of their reputation as one of London’s leading theatrical families in the early 1900s, but who are equally proud of their other profession. The Fitzglens pursue this second profession very discreetly indeed; unknown to most of Edwardian London, they are what they like to term society burglars.

The world is littered with a great many intriguing legends, of course, and most of the ones that thread England’s past in particular have a pleasing touch of eeriness. There are spectral coaches that rattle across ancient courtyards to herald a death – ghostly music from empty rooms – disgruntled apparitions demanding the righting of wrongs. There are grey ladies in old rectories, and occasionally even a mischievous gentleman in Elizabethan costume, hinting slyly that he knows where an undiscovered Shakespearean folio is buried.

But as well as that, there are stories of gifts allegedly bestowed by grateful monarchs on their subjects – bowls or cups or religious vessels, all beautiful, most valuable, but several that carry strange pledges or disquieting warnings. Out of this embarrassment of riches, for me, one legend stood out.

The Muncaster Luck.

The story goes that in the mid-1400s no less a person than Henry Vl gave to a noble Cumberland family a bowl, in gratitude to them for sheltering him during his exile after losing his Throne to Edward lV.

The family were the Penningtons of Muncaster Castle, and Henry’s gift to Sir John Pennington carried a pledge that the bowl held good fortune, and that as long as it was unbroken the Penningtons would prosper. That belief has survived from that century to this – as, remarkably, has the bowl itself.

A fragment of an old verse apparently promises:

“It shall bless thy bed, it shall bless thy board, They shall prosper by this token, In Muncaster Castle good luck shall be Till the charméd cup is broken.”

The story held out an alluring hand. But I thought that to use the Muncaster legend itself – especially as the bowl can still be viewed in Muncaster Castle – could be fraught with potential problems. Historical facts often have the annoying way of tripping up fictional events. But there seemed no reason why a whole new legend could not be created – that of a bowl, or, better still a chalice, in similar vein to the Muncaster Bowl, but with a dark back-story that would be all its own.

And so the the Talisman Chalice of the book came into being.

Rather than assign this fictional Chalice’s origins to the hapless Henry Vl, I arranged for it to make its first appearance in the company of Richard II, who already had a few robust tales in his armoury, and whose reputation I thought could probably take one more. By this point in the writing of the book, the Chalice itself had collected a few robust tales of its own, as well – most notably that anyone who possessed it ‘wrongfully’ would be dragged into a darkness ‘from which he or she would never emerge’. Which could be interpreted as a medieval warning to enterprising thieves that if the Chalice were to be stolen, a very bad fate would befall those who stole it.

All of which resulted in Jack Fitzglen attempting to uncover scandals and secrets, and to encounter a dark danger that was to threaten his beloved theatre of thieves.

Having dealt with the part of the story that would stretch across several centuries and encompass a few changes of royal dynastic rule – and having incorporated what promised to be a satisfying touch of the macabre into the mixture – there then came the matter of how the insouciant Fitzglens could actually track down the Chalice. Led by the inventive Jack, they could certainly explore scholarly documents and investigate academic lines of enquiry. But it seemed equally likely that they would hunt out clues within the raucous, often-scandalous Edwardian theatre world to which they belonged. Because mightn’t plays have been written about the Talisman Chalice? Or even songs? This latter idea was definitely a possibility. Music hall songs of that era often concealed all kinds of secrets, and a number of them frequently contained deeper meanings than might be apparent today. Many people know the famous, ‘My Old Dutch’, and the line about, ‘We’ve been together now for forty years/And it don’t seem a day too much’. But it’s perhaps not so widely known that the song was written as the husband’s farewell to his wife as they trudge up the hill to the workhouse, knowing that once there, they’ll be separated for the first time in all their forty years.

I greatly enjoyed making use of the wonderful music hall tradition of song-writing for this story, and I’m also immensely grateful to Henry Vl for giving the Pennington family the Muncaster Bowl – and in the process providing me with the base for the plot of Chalice of Darkness.

And I’m delighted that the Bowl itself is still at Muncaster Castle – still intact – and hopefully still containing the luck handed down by a long-ago King of England.

There are always decisions to be made during the writing of a book. Usually these are straightforward and familiar – for example, should a character be killed off in Chapter Three, or can the tension be stretched out until, say, Chapter Eight?

There are always decisions to be made during the writing of a book. Usually these are straightforward and familiar – for example, should a character be killed off in Chapter Three, or can the tension be stretched out until, say, Chapter Eight? The creation of a villain can be a surprisingly fascinating exercise. There are so many roles they can be allotted. For starters, it’s usually necessary – and hopefully interesting for the reader – to show their multi-layered lives, because they aren’t always stalking hapless heroines through fog-bound Victorian streets, or laying macabre traps for unwary widows with useful fortunes. They have to do ordinary things like collecting the dry-cleaning or going to the dentist. Applying for mortgages, perhaps: ‘Occupation, sir? A doctor? Oh, well, Dr Crippen, we’re always happy to lend money to members of the medical profession…’ Or,

The creation of a villain can be a surprisingly fascinating exercise. There are so many roles they can be allotted. For starters, it’s usually necessary – and hopefully interesting for the reader – to show their multi-layered lives, because they aren’t always stalking hapless heroines through fog-bound Victorian streets, or laying macabre traps for unwary widows with useful fortunes. They have to do ordinary things like collecting the dry-cleaning or going to the dentist. Applying for mortgages, perhaps: ‘Occupation, sir? A doctor? Oh, well, Dr Crippen, we’re always happy to lend money to members of the medical profession…’ Or,  If it’s to be a villainess, however, the author probably can’t do much better than base a killer on the seventeenth-century Hungarian countess,

If it’s to be a villainess, however, the author probably can’t do much better than base a killer on the seventeenth-century Hungarian countess,  chapters. Generally, a villain, no matter how charismatic or multi-layered, does have to be given his or her just deserts in the final chapter. It’s not exactly a convention that has to be observed, but it’s expected. Even if he/she isn’t tried and sentenced in the conventional manner, some kind of fate has to descend. This might cheat an author of writing a taut courtroom/prison cell scene, but it does open up a beautiful range of dramatic possibilities, including sending the culprit tumbling over the Reichenbach Falls, being submerged beneath the Paris Opera House, spontaneously combusting like Krook in Bleak House, or falling into the jaws of a crocodile as Captain Hook memorably did in Peter Pan. And Elizabeth Bathory got her come-uppance when she was bricked up in a lonely windowless room, in which she lived for four years.

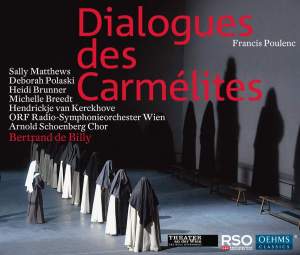

chapters. Generally, a villain, no matter how charismatic or multi-layered, does have to be given his or her just deserts in the final chapter. It’s not exactly a convention that has to be observed, but it’s expected. Even if he/she isn’t tried and sentenced in the conventional manner, some kind of fate has to descend. This might cheat an author of writing a taut courtroom/prison cell scene, but it does open up a beautiful range of dramatic possibilities, including sending the culprit tumbling over the Reichenbach Falls, being submerged beneath the Paris Opera House, spontaneously combusting like Krook in Bleak House, or falling into the jaws of a crocodile as Captain Hook memorably did in Peter Pan. And Elizabeth Bathory got her come-uppance when she was bricked up in a lonely windowless room, in which she lived for four years. I wasn’t expecting to find I had combined an ancient law and opera for a book, but Song of the Damned, (Book 3 of the Phineas Fox series), turned out to have both elements at its heart.

I wasn’t expecting to find I had combined an ancient law and opera for a book, but Song of the Damned, (Book 3 of the Phineas Fox series), turned out to have both elements at its heart. It relates the grim and emotionally-charged, true story of the imprisonment of sixteen Carmelite nuns during the French Revolution. They were captured because of their religious beliefs, and subsequently executed. The execution seems to have been an extraordinary piece of theatre – of which Poulenc makes full use. The nuns were forced to form a queue for the guillotine, and to mount the scaffold one by one, with the most junior novice being first. As they waited for death, they re-affirmed their religious vows aloud, and sang various hymns, (reports vary as to what the hymns actually were depending on which source you use). The singing was punctuated by the relentless fall of the guillotine for each nun, their voices gradually diminishing as each was beheaded, until, at the last, only the lone voice of the Mother Superior was to be heard. And then there was silence.

It relates the grim and emotionally-charged, true story of the imprisonment of sixteen Carmelite nuns during the French Revolution. They were captured because of their religious beliefs, and subsequently executed. The execution seems to have been an extraordinary piece of theatre – of which Poulenc makes full use. The nuns were forced to form a queue for the guillotine, and to mount the scaffold one by one, with the most junior novice being first. As they waited for death, they re-affirmed their religious vows aloud, and sang various hymns, (reports vary as to what the hymns actually were depending on which source you use). The singing was punctuated by the relentless fall of the guillotine for each nun, their voices gradually diminishing as each was beheaded, until, at the last, only the lone voice of the Mother Superior was to be heard. And then there was silence. And it seems that the word comes from the Old English infangene-þēof – ‘Thief seized within’ or ‘in-taken-thief’. Infangenthief or infangentheof, no matter how you spell it, was, an Anglo-Saxon arrangement, supposedly from the time of Edward the Confessor – c.1003-1066, and one of the last of the royal House of Wessex.

And it seems that the word comes from the Old English infangene-þēof – ‘Thief seized within’ or ‘in-taken-thief’. Infangenthief or infangentheof, no matter how you spell it, was, an Anglo-Saxon arrangement, supposedly from the time of Edward the Confessor – c.1003-1066, and one of the last of the royal House of Wessex. use of it as well. It helped keep the rebellious Saxons in their place. The law fell more or less into disuse in the fourteenth century and all-but vanished from England’s history. Except for the occasional name here and there. Like Infanger’s Field.

use of it as well. It helped keep the rebellious Saxons in their place. The law fell more or less into disuse in the fourteenth century and all-but vanished from England’s history. Except for the occasional name here and there. Like Infanger’s Field. Finishing the writing of any book is a curiously mixed experience. There’s a sense of achievement and even a muted delight because you finally got there. But there’s also hideous doubt, because although you got there, you’re no longer sure if it’s as good as it seemed when you exuberantly wrote ‘Chapter One’ about a year earlier. You’re also struggling to see a resemblance between the finished product, and the original synopsis your editor and your agent liked so much. You remember the famous line about characters: “You do everything you can to raise them right, and as soon as they hit the page, they do any damn thing they please.”

Finishing the writing of any book is a curiously mixed experience. There’s a sense of achievement and even a muted delight because you finally got there. But there’s also hideous doubt, because although you got there, you’re no longer sure if it’s as good as it seemed when you exuberantly wrote ‘Chapter One’ about a year earlier. You’re also struggling to see a resemblance between the finished product, and the original synopsis your editor and your agent liked so much. You remember the famous line about characters: “You do everything you can to raise them right, and as soon as they hit the page, they do any damn thing they please.” sitating a frantic rush to various computer shops to buy a new one and then an entire day trying fathom how it worked. When you finally did get it operating, at the end of the print run the entire ms slid off the desk and scattered itself everywhere. That entailed crawling around the floor, fielding 200+ out-of-sequence pages, and shuffling them into order. Inevitably, it took longer than it should have done, because you found yourself reading bits you had forgotten writing, and having to read on to find out what happened next. You then found a continuity error – characters knowing, and acting on, events before the events had actually happened. So you had to comb the entire text to put that right, then print the whole thing all over again.

sitating a frantic rush to various computer shops to buy a new one and then an entire day trying fathom how it worked. When you finally did get it operating, at the end of the print run the entire ms slid off the desk and scattered itself everywhere. That entailed crawling around the floor, fielding 200+ out-of-sequence pages, and shuffling them into order. Inevitably, it took longer than it should have done, because you found yourself reading bits you had forgotten writing, and having to read on to find out what happened next. You then found a continuity error – characters knowing, and acting on, events before the events had actually happened. So you had to comb the entire text to put that right, then print the whole thing all over again. That was when you decided it would be more restful to return to the desk and start writing another book.

That was when you decided it would be more restful to return to the desk and start writing another book. Music has frequently been a catalyst for me in the creating of a plot, and it seems to have found its way into a good many of my books. There’s the eerie death lament, ‘Thaisa’s Song’ in The Bell Tower, and the music hall songs in Ghost Song. More

Music has frequently been a catalyst for me in the creating of a plot, and it seems to have found its way into a good many of my books. There’s the eerie death lament, ‘Thaisa’s Song’ in The Bell Tower, and the music hall songs in Ghost Song. More  recently, there’s the Phineas Fox series, with a music historian and researcher as the central character – although it has to be said that while Phin certainly gets entangled in music mysteries, he also finds himself drawn into other intriguing situations

recently, there’s the Phineas Fox series, with a music historian and researcher as the central character – although it has to be said that while Phin certainly gets entangled in music mysteries, he also finds himself drawn into other intriguing situations the Piper of Hameln to draw on – that infamous figure from the Middle Ages, who, when the townspeople reneged on payment for his rat-catching services, wrought his grisly revenge by luring the children into the mountains by his magical music. You do have to be wary of sinister strangers offering peculiar deals, although the legend has certainly provided material for such diverse names as the Brothers Grimm, Robert Browning, and Walt Disney.

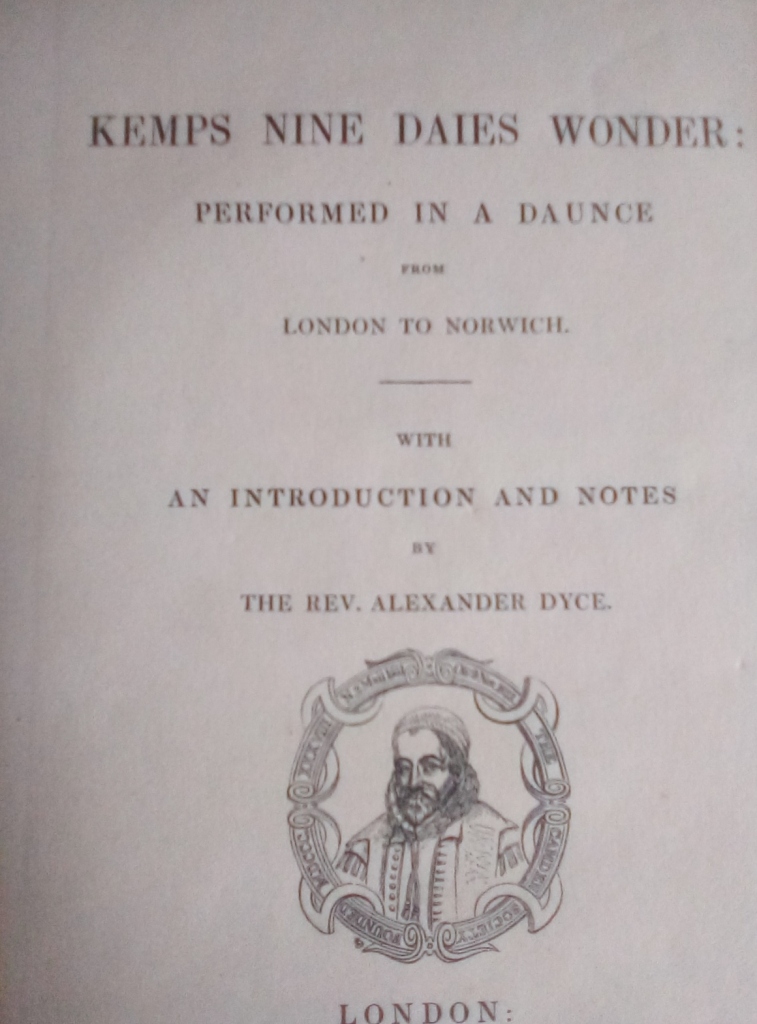

the Piper of Hameln to draw on – that infamous figure from the Middle Ages, who, when the townspeople reneged on payment for his rat-catching services, wrought his grisly revenge by luring the children into the mountains by his magical music. You do have to be wary of sinister strangers offering peculiar deals, although the legend has certainly provided material for such diverse names as the Brothers Grimm, Robert Browning, and Walt Disney. caperings of one Will Kemp. Master Kemp was a Shakespearean comic actor and ‘purveyor of mad jests and merry jigs’, and he accepted a bet that he could not dance from London to Norwich – roughly 80 miles (132 km). He won the bet, although it took him nine days to do it – which he later chronicled as ‘The Nine Daie’s Wonder’ [sic]. Happily, though, the nine days don’t seem to have been entirely without a few lighter moments; one version tells how, at one part of his journey, a young lady came out and danced a mile with him, to keep him company. Some versions suggest slyly that caperings of a different kind took place, as well. But that would be a tale for an entirely different kind of book, and in any case, Shakespeare, if he heard about his actor’s exploits, would have instantly spotted the potential for a bawdy romp scene, and very likely used a version of it in several of the plays. (He probably did just that, although probably not in Hamlet or King Lear).

caperings of one Will Kemp. Master Kemp was a Shakespearean comic actor and ‘purveyor of mad jests and merry jigs’, and he accepted a bet that he could not dance from London to Norwich – roughly 80 miles (132 km). He won the bet, although it took him nine days to do it – which he later chronicled as ‘The Nine Daie’s Wonder’ [sic]. Happily, though, the nine days don’t seem to have been entirely without a few lighter moments; one version tells how, at one part of his journey, a young lady came out and danced a mile with him, to keep him company. Some versions suggest slyly that caperings of a different kind took place, as well. But that would be a tale for an entirely different kind of book, and in any case, Shakespeare, if he heard about his actor’s exploits, would have instantly spotted the potential for a bawdy romp scene, and very likely used a version of it in several of the plays. (He probably did just that, although probably not in Hamlet or King Lear). There’s a sense of familiarity and reassurance in much-read copies of books by favourite authors. It’s comforting to turn a page and remember that this is the part where you spilled soup on the name of the murderer because last time you read it you had flu and were under a blanket on the sofa. Or to realise you’re coming up to the part where you dropped the book in the bath, and that the renunciation scene between the lovers is permanently scented with Imperial Leather. Even better, is embarking on the chapter detailing the villain’s midnight prowl through the dark old house, where the pages are spattered with hair dye, because you were trying to put magenta streaks in your hair, and you had 15 minutes to fill up while the colour soaked in.

There’s a sense of familiarity and reassurance in much-read copies of books by favourite authors. It’s comforting to turn a page and remember that this is the part where you spilled soup on the name of the murderer because last time you read it you had flu and were under a blanket on the sofa. Or to realise you’re coming up to the part where you dropped the book in the bath, and that the renunciation scene between the lovers is permanently scented with Imperial Leather. Even better, is embarking on the chapter detailing the villain’s midnight prowl through the dark old house, where the pages are spattered with hair dye, because you were trying to put magenta streaks in your hair, and you had 15 minutes to fill up while the colour soaked in. Once upon a time there were secondhand bookshops – marvellous places with creaking floorboards and intriguing cobwebby corners. You could spend hours in them, searching for lost titles by long-ago authors. Often it was a good idea to take a few sandwiches and a flask with you, cancelling all engagements for the rest of the week.

Once upon a time there were secondhand bookshops – marvellous places with creaking floorboards and intriguing cobwebby corners. You could spend hours in them, searching for lost titles by long-ago authors. Often it was a good idea to take a few sandwiches and a flask with you, cancelling all engagements for the rest of the week.